Pain as a metaphor....Part 2

“An unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage”

”

If pain is not necessarily associated with tissue damage as was discussed in part 1 then where does that leave us. The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) definition has been included at the top of this page again for review.

This is an area myself and Ben really chewed the fat on through my 2016 mentorship. Ben released some FREE PAIN RESOURCES on the topic, they will be integrated here for my readers.

"Pain has the function of providing a warning system to protect our bodies from harm. It serves a key purpose to our ongoing survival by protecting us from harmful stimulus and situations. It is, in its most basic form , a threat detection system.

Figure 1. Descartes (1890) original linear theory of pain being triggered by putting foot in fire then literally ringing a 'pain bell' in the brain as it is received from the tissues. We now know this linear uncomplicated system to be highly inaccurate.

Pain historically has been seen as a relatively uncomplicated process with an input arising from the tissue and being reproduced in the experience of pain as being an accurate indication of the tissue state (Figure 1). More recently pain has started to be seen as not providing an accurate representation of the state of tissue, or the end of linear system, but instead being modulated by many factors including beliefs and previous experiences, mood and emotion, social and environmental, stress, attention and sensory stimulation.

Pain is a reflection that reflects previous experiences, the present situation and our current biological state.

A modern view of pain is a multifaceted experience that comprises of a sensory / discriminative component providing intensity and location and an affective / behavioural component that influences emotion, attention and actions related to pain or the avoidance of pain.

As pain persists beyond the normal time of tissue healing, the neuroanatomical and neurophysiological processes that are used in the experience of pain can change at the periphery, spinal cord and brain levels meaning that the pain we experience can have less to do with the physical state of the tissue, and more to do with the threat detection system itself."

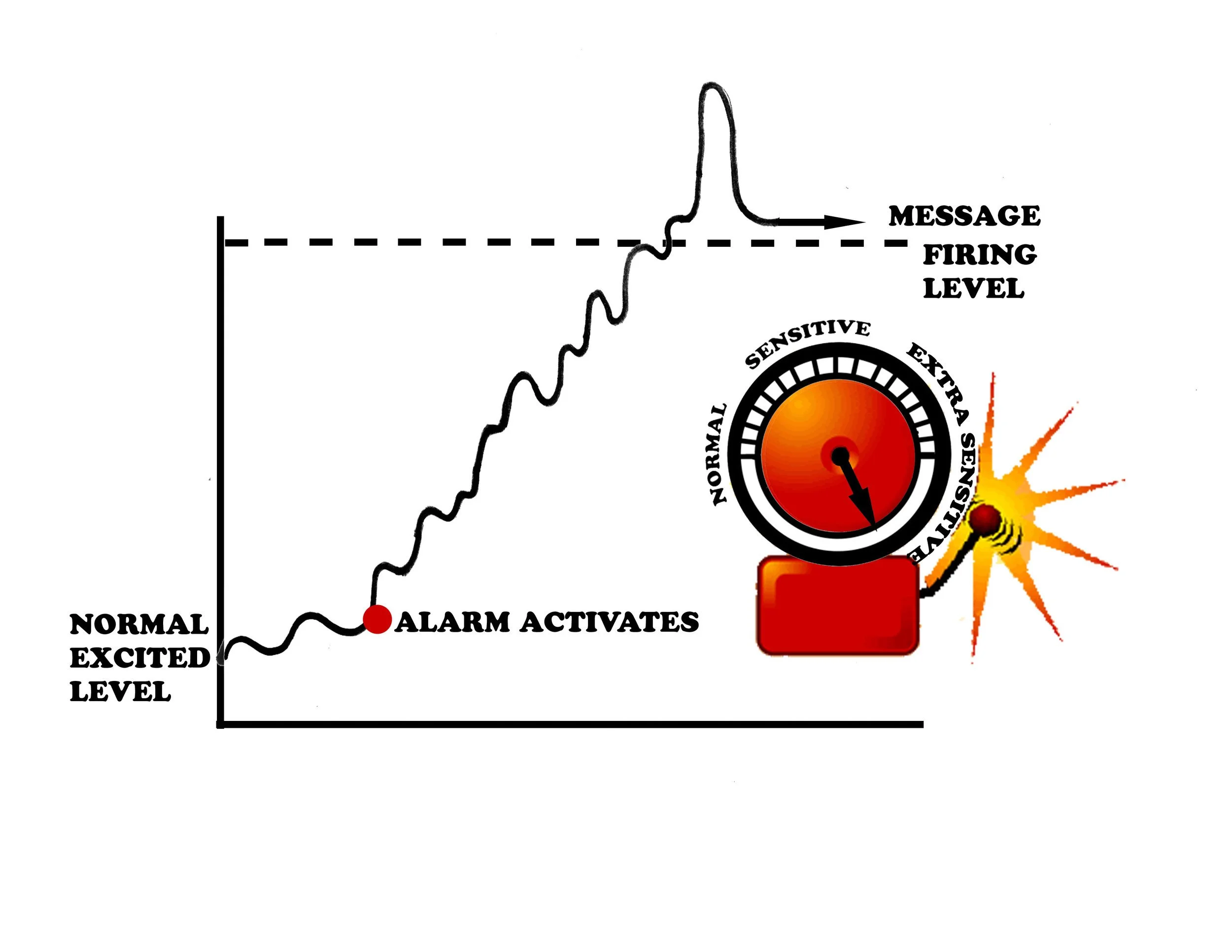

Figure 2: Pain as an "alarm". All our tissues have a nerve supply which has a constant low level buzz of electricity. When the alarm is triggered that electricity shoots and a signal is passed up to the brain to 'potentially' bring about the experience of pain.

*Image kindly reproduced with permission from Louw & Puentedura (2013)

More simply put, pain is healthy and unavoidable. It is something that the overwhelming majority of us will experience at multiple joints in our lives and without it we would be in danger of pretty serious damage. Pain is essentially a positive thing providing us with protection, unfortunately sometimes it can become "over" protective and work a bit too well.

Fortunately it can be altered by understanding more about the process and managing many aspects of our lives that contribute to what we feel and think.

Helping people understand more about their experience of pain can be helpful in reducing it.

Pain is aptly described as an "alarm system" and sometimes the "alarm" can become too sensitive and is triggered very easily (Figure 2). The alarm can be desensitised by many factors including previous injury and pain, our beliefs about our bodies and our current mood and stress levels.

Persistent or chronic pain his often more to do with changes within the "alarm system" rather than a faithful reflection of the current physical state of our bodies."

*All content in italics is directly taken from Ben's fantastic free pain resource available following the link.

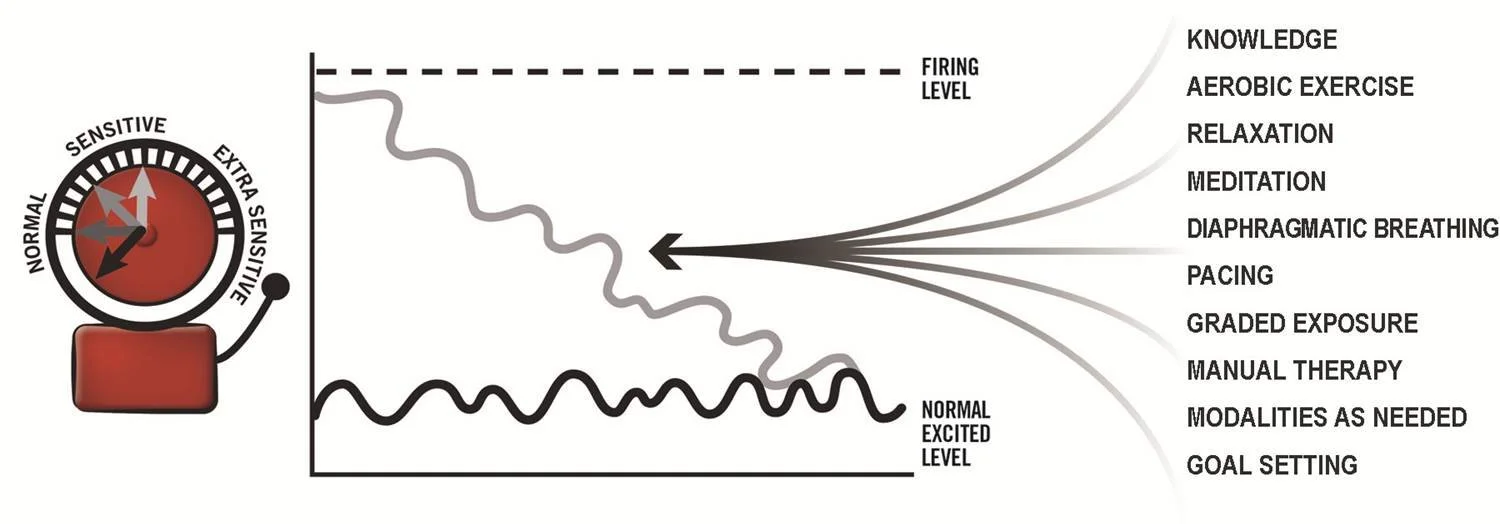

Figure 3: Some of the factors that have been shown to desensitise the alarm once activated.

*Image kindly reproduced with permission from Louw & Puentedura (2013).

There are a host of things we as clinicians can do to help you desensitise the alarm that first and foremost includes reassuring you it is safe to get going and hurt does not necessarily equal harm (knowledge). We can help you get started with aerobic exercise as this has been shown to be useful. We can help you 'pace' yourself so you don't overdo it and trigger the alarm, starting really super easy and progressing over time with clear structured goals (Graded exposure to achieve them). We can help you to relax and learn strategies that enable you to do this on your own (meditation, mindfulness, diaphragmatic breathing....).

The process of desensitising an alarm requires a really strong bond between both patient and clinician, we call this the 'therapeutic alliance'. The only caveat with this is that we do not want to create too much of a dependency on us as clinicians. Self-efficacy, or the ability to self manage should always be the ultimate end goal and is why this process has to be an active one, you as the patient will not expect someone to solve this for you, I as the clinician must provide you all the tools to fully equip you along the way. Ben likens this to a back seat driver approach, you are driver, I am passenger. Manual therapy or (modalities as needed) may help us achieve this end goal but as soon as we can facilitate the process without touching you, the better. All those words in bold can be seen desensitising the alarm in figure 3.

To continue your journey in understanding the neurophysiology of pain, move on to part 3 :)

Luke R. Davies

REFERENCES

Louw, A. and Puentedura, E. (2013). Therapeutic Neuroscience Education; Teaching Patients About Pain, International Spine and Pain Institute, USA.

Cormack, B. (2016). FREE PAIN RESOURCE accesible at: http://www.cor-kinetic.com/free-pain-resource-download-now/

Bens list:

Melzack, R. and Katz, J. (2012). Pain, Wires: Cognitive Science, 4(1), P.1-15.

Melzack, R. (2001). Pain and the Neuromatrix in the Brain, J Dent Educ, 65(12), P.1378-82.

Louw, A., Zimney, K., O'Hotto, C. and Hilton, S. (2016). The Clinical Application of Teaching People about Pain, Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 32(5), P385-95.